Software development methodologies describe the structured approach used to plan, build, test, and deliver software solutions. They influence how teams make decisions, collaborate across roles, manage risk, and balance scope, time, cost, and quality. Understanding how these methodologies work makes it easier to choose an approach that aligns with a project’s needs, an organization’s capabilities, and its business objectives.

What are software development methodologies?

Software development methodologies are operating models for delivering software. They define how work flows from idea to release, how responsibilities are distributed, and how progress and quality are evaluated over time.

Rather than specifying tools or technologies, methodologies establish:

- How requirements are discovered and refined

- How work is planned and sequenced

- How feedback is incorporated

- How change, risk, and dependencies are managed

In practice, a methodology acts as a shared contract between engineering, product, and business stakeholders on how work gets done.

Purpose and value of software development methodologies

The primary purpose of a methodology is to reduce uncertainty in complex software initiatives. Software projects operate under shifting requirements, technical uncertainty, and human coordination challenges. Methodologies provide a repeatable structure for navigating that uncertainty.

Specifically, they help teams:

- Create alignment across roles with different incentives and perspectives

- Make trade-offs between scope, time, cost, and quality explicit

- Surface risks early through defined checkpoints or feedback loops

- Maintain delivery momentum as complexity increases

At scale, methodologies also function as an organizational backbone, enabling consistency across teams while still allowing for local adaptation.

Structural limitations of software development methodologies

Every methodology embeds assumptions about team maturity, problem stability, and organizational context. When those assumptions do not hold, the methodology itself can become a source of friction.

Common limitations include:

- Process rigidity in environments that require rapid adaptation

- Excessive overhead relative to project size or risk profile

- False confidence created by following rituals without outcomes

- Tension between standardized processes and team autonomy

Methodologies fail not because they are “wrong,” but because they are applied without regard for context. Effective use requires understanding why practices exist — not just how to execute them.

Why teams adopt a software development methodology

Adopting a methodology is primarily about coordination and scalability, not control. As projects grow in scope, duration, or stakeholder count, informal ways of working break down.

A defined methodology introduces stability in environments where variability would otherwise dominate. It creates predictable interaction points for planning and review, establishes common terminology for progress and risk, and provides decision-making guardrails when pressure increases.

This becomes especially important when delivery is organized around structured execution models such as a dedicated development team, where consistency and role clarity are critical to scale.

Organizational and team-level benefits

At the team level, methodologies clarify expectations around ownership, communication, and delivery rhythm. This reduces dependency friction and cognitive load, especially in cross-functional setups.

At the organizational level, the benefits compound. Consistent methodologies enable more reliable forecasting, smoother onboarding, and better alignment between product strategy and engineering execution. They also make delivery processes observable and measurable, which is a prerequisite for meaningful improvement over time.

Methodologies also enable continuous improvement by creating stable processes that can be measured and refined over time.

Impact on quality, cost, and time to market

Methodological choices directly affect delivery outcomes:

- Quality is influenced by when and how validation occurs

- Cost is shaped by rework, change management, and coordination overhead

- Time to market depends on sequencing, feedback loops, and decision latency

For example, methodologies that defer testing increase late-stage risk, while those that support incremental validation tend to surface issues earlier, when changes are less expensive. The methodology defines where risk accumulates and where it is reduced.

Main categories of software development methodologies

At a high level, most approaches fall into three categories: Agile, Sequential, and Hybrid. These categories represent fundamentally different assumptions about uncertainty, change, and control in software delivery.

The choice between them determines how work is planned, how teams collaborate, how risk is managed, and when decisions become difficult or expensive to reverse. Understanding these differences is essential for evaluating suitability beyond surface-level labels.

Sequential methodologies

Sequential methodologies are based on the premise that a problem can be sufficiently understood before development begins. They emphasize upfront analysis, detailed planning, and clearly delineated phases, each with defined outputs and approval points.

Work progresses in a linear sequence, and transitions between phases are typically gated. This structure prioritizes predictability and control, particularly in environments where scope stability, documentation, and compliance are critical. Decisions made early in the lifecycle carry significant weight, as revisiting them later often incurs substantial cost.

Risk management in sequential models is concentrated in early stages. Considerable effort is invested in requirements definition and design to minimize downstream uncertainty. As a result, visibility into final outcomes is deferred until later phases, increasing the importance of the accuracy of initial assumptions.

Sequential approaches are most effective when requirements are stable, stakeholder expectations are fixed, and the cost of change must be tightly controlled through formal governance rather than continuous adjustment.

Agile methodologies

Agile methodologies are built around the assumption that change is inevitable and that learning occurs throughout development, not before it. Rather than attempting to define a complete solution upfront, Agile approaches structure work into short cycles that allow teams to validate assumptions, incorporate feedback, and adjust priorities continuously.

Planning in Agile environments is incremental and adaptive. Requirements are refined progressively, and delivery is organized around producing working software at regular intervals. This shifts emphasis away from predictive accuracy and toward responsiveness and transparency. Progress is measured through demonstrable outcomes rather than adherence to long-term plans.

From an organizational perspective, Agile methodologies redistribute control. Decision-making authority is pushed closer to delivery teams, while stakeholders remain engaged through frequent review and feedback loops. This enables a faster response to market or technical signals but also requires disciplined collaboration, clear product ownership, and tolerance for evolving scope.

Agile performs best in domains where requirements are expected to change, customer feedback is accessible, and teams have sufficient autonomy and technical maturity to manage frequent iteration without accumulating instability.

Hybrid methodologies

Hybrid methodologies emerge from the recognition that neither strict predictability nor unrestricted adaptability is sufficient for many real-world projects. These approaches combine structured planning and governance with iterative execution, allowing different parts of the lifecycle to operate under different control models.

The primary value of hybrid methodologies lies in selective rigor. Rather than enforcing a single delivery philosophy, they allow teams to align practices with risk profiles, dependency structures, and organizational constraints.

In practice, hybrid methodologies are often paired with flexible resourcing strategies, especially when organizations combine internal teams with external support through models such as staff augmentation or project-based outsourcing.

Sequential software development methodologies

Sequential approaches organize work around phase completion rather than incremental value delivery. Each stage produces formal artifacts — requirements specifications, design documents, test plans — that serve as inputs to the next phase and as reference points for validation and accountability.

Progress is governed through:

- phase gates and formal approvals

- documented baselines for scope and design

- traceability between requirements, implementation, and verification activities

Because downstream activities depend heavily on upstream outputs, early-stage decisions strongly constrain later options. As a result, architectural and requirement errors tend to propagate forward unless detected through rigorous review processes.

Advantages and structural constraints

The strength of sequential methodologies lies in their ability to stabilize execution through foresight. By front-loading analysis and documentation, they enable:

- strong alignment between contractual scope and delivery obligations

- clear accountability through documented decisions

- simplified compliance and audit processes

- predictable coordination across large or distributed teams

However, this stability comes at a cost. Sequential models accumulate risk rather than distributing it, particularly when assumptions prove incorrect. Limitations typically emerge in the form of:

- delayed feedback on functional and usability concerns

- reduced responsiveness to evolving stakeholder needs

- escalating rework costs as changes surface late in the lifecycle

- tension between formal change control and practical delivery needs

Sequential methodologies are most effective when system behavior can be precisely defined upfront and when the cost of change exceeds the cost of extensive early analysis. When uncertainty is higher, their rigid structure can shift risk downstream rather than eliminating it.

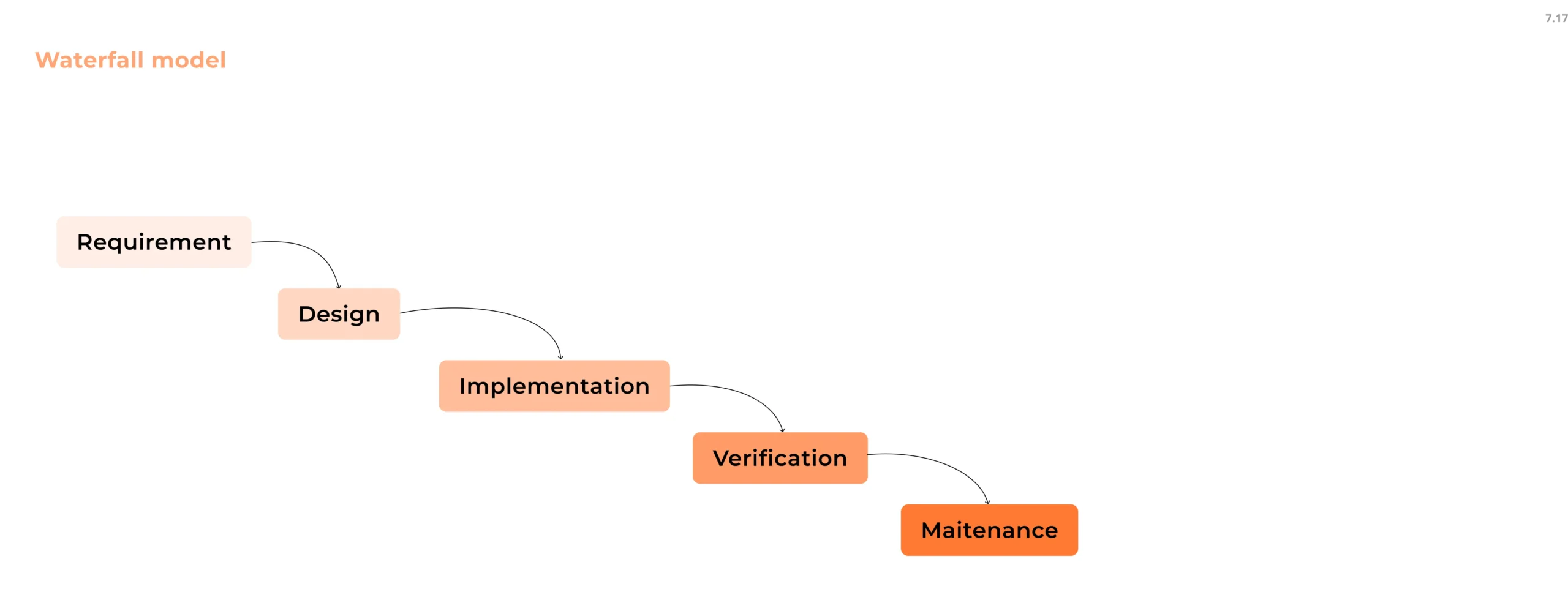

Waterfall methodology

The waterfall methodology is a sequential, plan-driven approach to software development in which progress flows through a fixed series of stages. Its defining principle is that key decisions about scope, architecture, and behavior are made upfront, and execution proceeds against those decisions with minimal deviation.

The model is commonly traced back to Winston W. Royce’s 1970 paper on managing large software systems, which analyzed the risks of purely linear development while emphasizing disciplined planning and verification. Although the term “waterfall” was applied later, the paper established the foundation for a structured, document-driven lifecycle that would shape enterprise software delivery for decades.

Key stages of the waterfall model

Requirements definition

This phase establishes what the system must do and under which constraints. Functional and non-functional requirements are documented in sufficient detail to support downstream design and validation. The emphasis is on completeness, consistency, and traceability rather than implementation detail.

System and solution design

Requirements are translated into architecture, component structures, data models, and interfaces. Design decisions made here largely determine system scalability, maintainability, and performance characteristics. In waterfall, design serves as a binding contract for implementation.

Implementation

Development teams build the system according to the approved design specifications. Work is typically decomposed into well-defined tasks with limited ambiguity. Unit-level verification may occur, but broader validation is deferred until later stages.

Verification and validation

Testing focuses on confirming that the implemented system conforms to documented requirements and design assumptions. Because functional feedback arrives late, defects discovered here often have higher remediation costs.

Maintenance

Post-release activity includes defect correction, environment adaptation, and controlled enhancements. Changes are handled through formal change management processes to preserve system integrity and documentation alignment.

The dependency between phases is intentional: each stage assumes the correctness of the previous one, which is both the model’s strength and its primary risk.

Early testing in waterfall

Although testing is traditionally positioned late in the lifecycle, mature waterfall implementations mitigate risk through early verification activities. These do not replace later testing but aim to prevent defects from being embedded in design and requirements. Early testing typically includes:

- systematic reviews of requirements for ambiguity, inconsistency, and testability

- validation of design artifacts against functional and quality objectives

- early test planning aligned with requirement specifications

By shifting quality assurance upstream, organizations reduce the likelihood of structural defects that are expensive or impossible to correct during verification. This practice does not make waterfall iterative; it redistributes risk earlier in the lifecycle when corrective action is cheaper.

When waterfall is the right choice

Waterfall is most effective in environments where uncertainty is low and constraints are high. Typical characteristics include:

- stable, well-understood requirements

- strict regulatory or contractual obligations

- strong emphasis on documentation and auditability

- limited tolerance for mid-project change

In these contexts, the cost of extensive upfront analysis is often justified by reduced execution risk and clearer accountability.

Limitations of the waterfall approach

Waterfall concentrates risk rather than spreading it. Because feedback loops are delayed, incorrect assumptions can persist until late-stage validation, where correction is costly and disruptive. Structural limitations include:

- high cost of change after requirements and design are baselined

- limited stakeholder feedback during implementation

- reduced adaptability to evolving business or technical conditions

- tendency toward schedule pressure near phase boundaries

For systems with significant discovery, innovation, or behavioral uncertainty, these characteristics can outweigh the benefits of predictability.

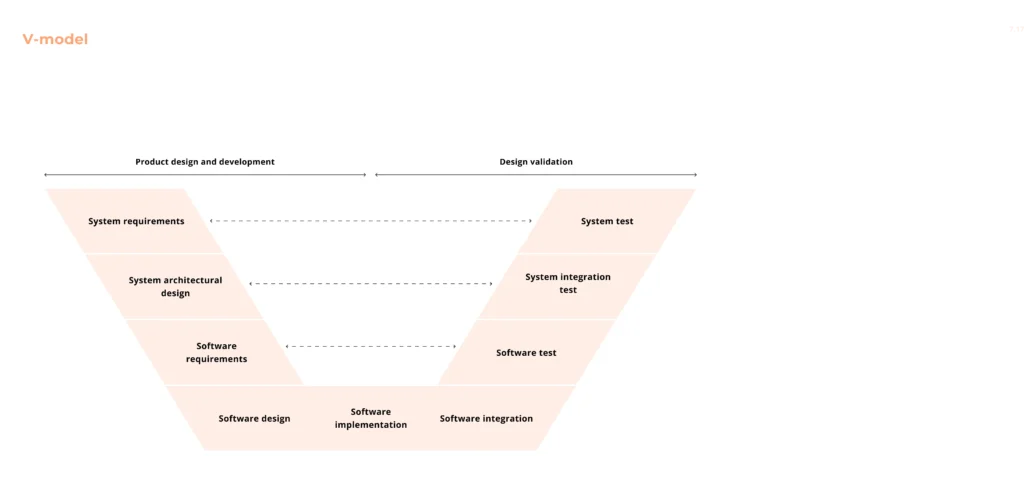

V-model methodology

The V-model is a disciplined extension of the waterfall methodology that explicitly integrates testing and validation into every development phase. Its defining characteristic is the direct mapping between specification activities and corresponding testing activities, creating a strong emphasis on traceability and early quality assurance.

Development progresses down the left side of the “V” through requirements and design, while testing progresses up the right side through validation stages that mirror those earlier decisions. Test planning begins as soon as requirements and designs are defined, rather than being deferred until implementation is complete.

The V-model is especially effective in environments where verification rigor, compliance, and predictability outweigh the need for flexibility.

Key characteristics

- One-to-one alignment between development phases and testing phases

- Early definition of test cases based on requirements and design artifacts

- Strong documentation and traceability between requirements, code, and tests

When the V-model is appropriate

- Systems with strict reliability or safety requirements

- Projects requiring formal verification and validation

- Domains such as embedded systems, automotive, aerospace, and healthcare

Limitations

- High rigidity and limited tolerance for changing requirements

- Significant upfront effort in documentation and test planning

- Poor fit for exploratory or rapidly evolving products

Incremental development model

The incremental process model builds software in controlled, functional increments, rather than delivering the entire system at once. Each increment adds a clearly defined set of features to an existing, working baseline, allowing teams to deliver value early while maintaining a structured development flow.

Instead of locking all requirements upfront, the system evolves through multiple planned releases, with each increment passing through analysis, design, development, testing, and deployment. Earlier increments typically focus on core functionality, while later ones extend capabilities based on priorities and feedback.

Key characteristics of the model

- Delivery of usable software early in the lifecycle

- Progressive expansion of system functionality

- Feedback-driven refinement between releases

- A balance between upfront planning and iterative execution

This approach reduces risk by validating assumptions incrementally and surfacing issues earlier than fully sequential models.

The incremental model works best when

- Core requirements are known, but details may evolve

- Early market or stakeholder feedback is valuable

- The project timeline is long or the complexity is moderate to high

- Features can be logically partitioned and delivered independently

Limitations to consider

- Strong architectural planning required to avoid integration issues

- Repeated testing and integration that can increase overhead

- Inexperienced teams or poorly defined system boundaries

In practice, the incremental model often serves as a bridge between strict sequential approaches and fully adaptive methodologies, delivering value earlier without abandoning process discipline.

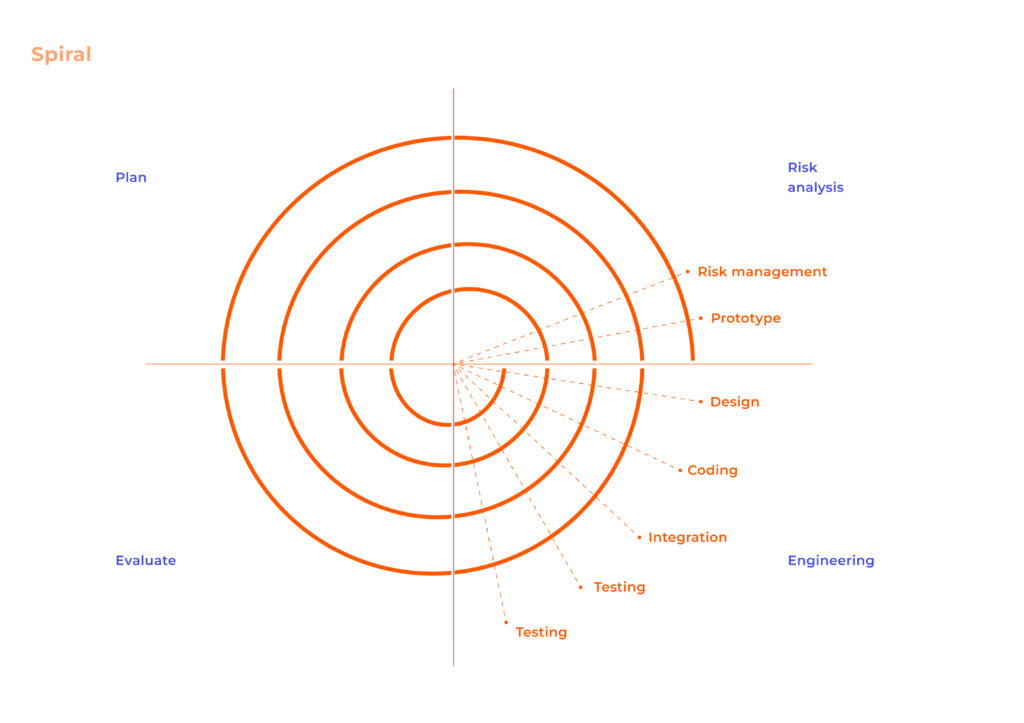

Spiral model

The spiral model is a risk-driven, iterative methodology designed for large, complex, and high-uncertainty projects. Development proceeds through a series of loops, or spirals, each representing a complete cycle of planning, risk analysis, implementation, and evaluation.

Unlike linear or purely incremental models, progress is governed by risk resolution rather than phase completion. Prototyping is frequently used to reduce technical, performance, or usability risks before committing to full implementation.

The spiral model functions as a meta-framework, capable of incorporating techniques from other methodologies when appropriate.

Key characteristics

- Iterative development structured around explicit risk assessment

- Continuous stakeholder evaluation at the end of each cycle

- Flexible scope refinement based on validated learning

When the spiral model is appropriate

- Large-scale systems with significant technical or business risk

- Projects with unclear or evolving requirements

- Long-term initiatives where cost and feasibility must be reassessed regularly

Limitations

- High management and planning overhead

- Dependence on strong risk analysis expertise

- Small or low-risk projects due to cost and complexity

Prototype-based development

Prototype-based development focuses on building early representations of a system to clarify requirements, validate assumptions, and reduce uncertainty before committing to full-scale development. Prototypes may be disposable or evolved into the final system, depending on the chosen approach.

This methodology is particularly effective when user needs are unclear, requirements are unstable, or usability and interaction design are critical success factors.

Prototyping shifts validation forward in the lifecycle by replacing abstract specifications with tangible artifacts.

Key characteristics

- Early, iterative feedback from users and stakeholders

- Emphasis on requirement discovery and refinement

- Strong alignment between product intent and user expectations

Common prototyping approaches

- Throwaway prototyping to explore ideas without long-term constraints

- Evolutionary prototyping that incrementally becomes the final system

- Incremental prototyping across system components

Prototype-based development is appropriate for

- Projects with high uncertainty around requirements

- User-facing systems with complex workflows or interactions

- Early feasibility validation for novel or high-risk concepts

Limitations

- Risk of scope creep driven by continuous feedback

- Potential confusion between prototype and production-ready software

- Additional time and cost if prototypes are poorly governed

Agile software development methodologies

Agile software development methodologies represent a family of iterative and incremental approaches designed to manage uncertainty, accelerate feedback loops, and continuously align delivery with evolving business needs. Rather than prescribing a fixed sequence of phases, Agile frameworks emphasize short planning horizons, empirical decision-making, and close collaboration between engineering teams and stakeholders.

Agile is not a single methodology but an umbrella that includes multiple frameworks and practices, each addressing different organizational scales, product complexities, and delivery constraints.

Agile mindset and core concepts

At its core, Agile is grounded in an empirical mindset: decisions are driven by observed outcomes rather than upfront assumptions. Progress is evaluated through working software, and plans are continuously refined based on feedback, performance data, and changing constraints.

Agile frameworks operationalize this mindset through time-boxed iterations, cross-functional teams, incremental delivery, and continuous validation of assumptions — both technical and business-related.

Because Agile redistributes decision-making closer to delivery teams, leadership roles must evolve from directive control to enablement and systems thinking — a shift explored in The Agile Evolution of the Engineering Manager.

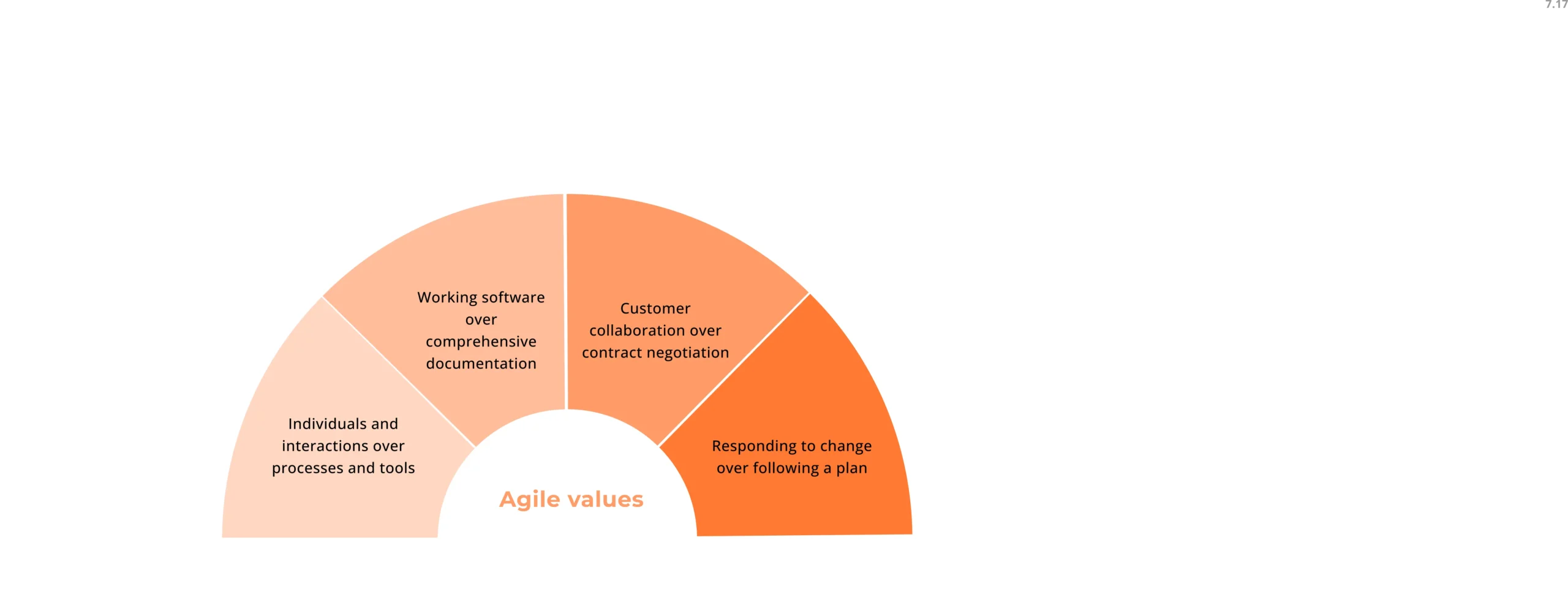

Four values of the Agile Manifesto

The Agile Manifesto defines four value statements that guide trade-off decisions rather than enforce rigid rules.

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools: prioritizes team autonomy, collaboration, and direct communication when process rigidity becomes counterproductive.

Working software over comprehensive documentation: treats executable software as the primary evidence of progress, while maintaining documentation only where it adds operational or regulatory value.

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation: encourages ongoing stakeholder involvement to refine scope and priorities as knowledge evolves.

Responding to change over following a plan: accepts change as an expected condition rather than a failure of planning.

Twelve principles of agile development

The twelve Agile principles translate the manifesto values into operational guidance. Collectively, they emphasize:

- Early and frequent delivery of valuable software

- Continuous accommodation of changing requirements

- Close collaboration between business and engineering

- Sustainable development pace and technical excellence

- Simplicity, self-organization, and regular process adaptation

For experienced teams, these principles function less as rules and more as a diagnostic lens for evaluating delivery effectiveness and organizational friction.

Advantages and limitations of Agile methodologies

Advantages

- Short feedback cycles reduce the risk of late-stage misalignment

- Incremental delivery enables earlier realization of business value

- Continuous stakeholder involvement improves requirement accuracy

- Technical issues surface earlier through continuous integration and testing

Limitations

- Long-term predictability of scope, cost, and timelines is inherently constrained

- High reliance on team maturity, discipline, and communication quality

- Reduced emphasis on formal documentation can complicate compliance or handover

- Ineffective governance can lead to scope creep and delivery fragmentation

Agile methods amplify both strengths and weaknesses of teams; they do not compensate for poor engineering practices or unclear product ownership.

How AI is extending Agile practices

AI is finding its place inside Agile teams through everyday work rather than bold transformations. It helps teams keep sprint discussions from disappearing, makes patterns in ongoing work easier to see, and reduces the backlog clutter that slowly slows delivery. Teams experience AI adoption as fewer interruptions, clearer conversations, and less effort spent maintaining process artifacts that no longer reflect reality.

What determines whether this helps or hinders delivery is not the tool itself, but how firmly ownership stays with the team. Observations from How AI Is Quietly Reshaping Agile: Lessons from the Field point to a consistent dynamic: when teams treat AI output as provisional and editable, it strengthens judgment rather than eroding it. Planning becomes sharper because context is preserved, retrospectives become more honest because patterns are harder to ignore, and flow improves because attention shifts away from administration and back toward delivery.

Popular agile frameworks

Scrum

Scrum establishes a lightweight governance model that relies on empiricism — transparency, inspection, and adaptation — to guide decision-making. Work is delivered in fixed-length iterations (sprints), during which scope is negotiated continuously while time and team capacity remain stable. This inversion of traditional project controls enables frequent validation of assumptions, earlier risk exposure, and incremental value delivery.

Roles, ceremonies, and artifacts

Roles

- The product owner owns outcome accountability, translating business objectives into an ordered product backlog and making prioritization decisions that maximize value under constrained capacity.

- The Scrum master acts as a process steward, ensuring adherence to Scrum principles, facilitating events, and addressing systemic impediments rather than directing execution.

- The development team is a self-managing, cross-functional unit responsible for converting backlog items into a potentially releasable increment, collectively owning quality, estimates, and delivery commitments.

Ceremonies

Scrum events create a recurring inspection and decision-making cadence:

- Sprint planning: establishes sprint goals and aligns backlog selection with team capacity.

- Daily Scrum: synchronizes execution and exposes blockers affecting sprint progress.

- Sprint review: evaluates delivered increments against stakeholder expectations.

- Sprint retrospective: drives continuous improvement of process, collaboration, and technical practices.

Artifacts

Artifacts provide transparency into scope, progress, and quality:

- Product backlog: an ordered representation of all known product work.

- Sprint backlog: the team’s commitment and execution plan for the current sprint.

- Increment: integrated work that meets the agreed definition of done.

Advantages of Scrum

- Enables rapid feedback through short delivery cycles and frequent review points

- Supports incremental discovery and validation of product direction

- Establishes clear accountability without imposing heavy process overhead

- Encourages continuous improvement through structured reflection

- Surfaces risk early by integrating inspection into execution

Disadvantages of Scrum

- Fixed sprint boundaries limit responsiveness to urgent or interrupt-driven work

- Ceremony overhead can outweigh benefits if facilitation is weak

- Requires strong product ownership and team maturity to function effectively

- Can lead to rigid interpretations that undermine adaptability

- Less suitable for work dominated by continuous flow rather than iteration

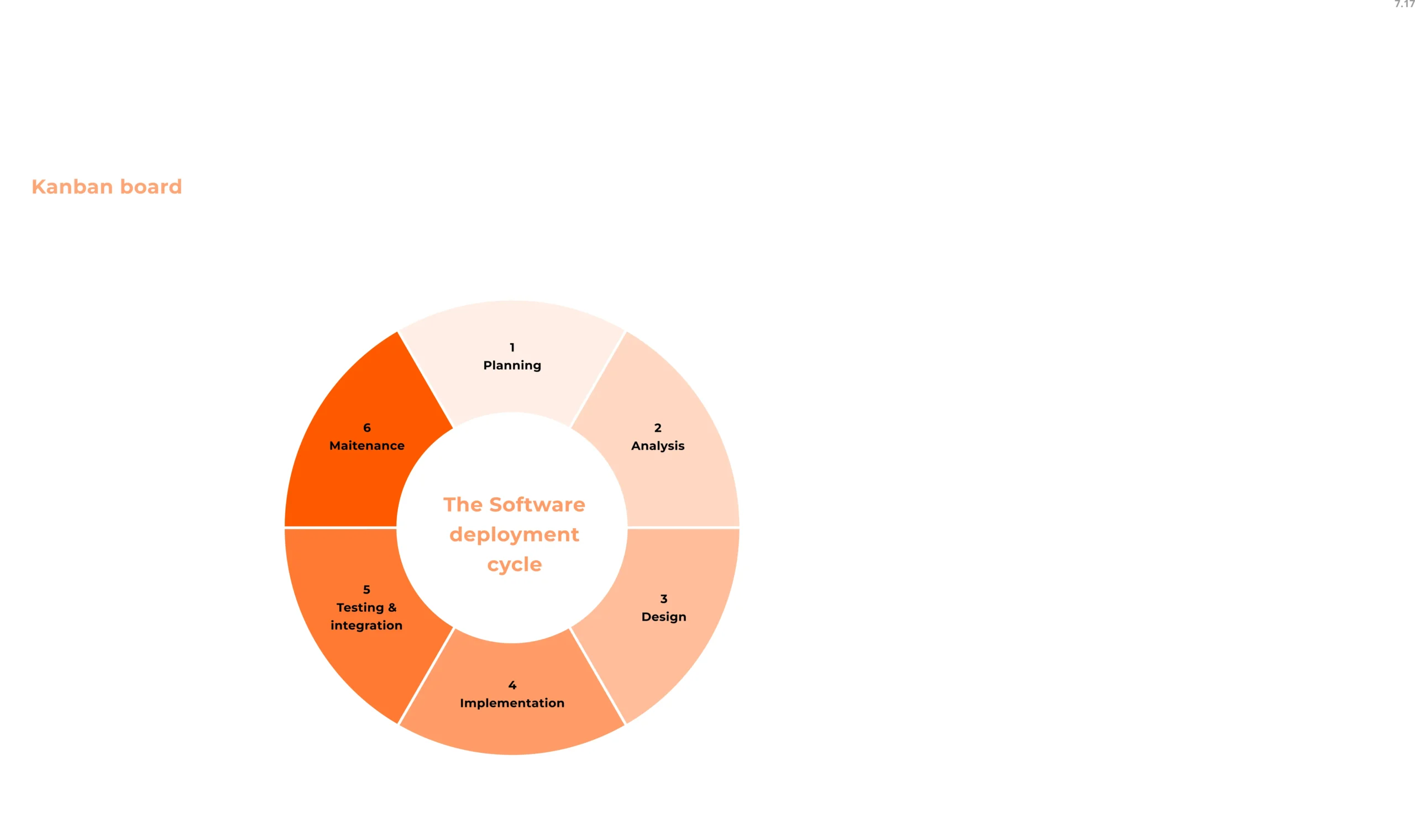

Kanban

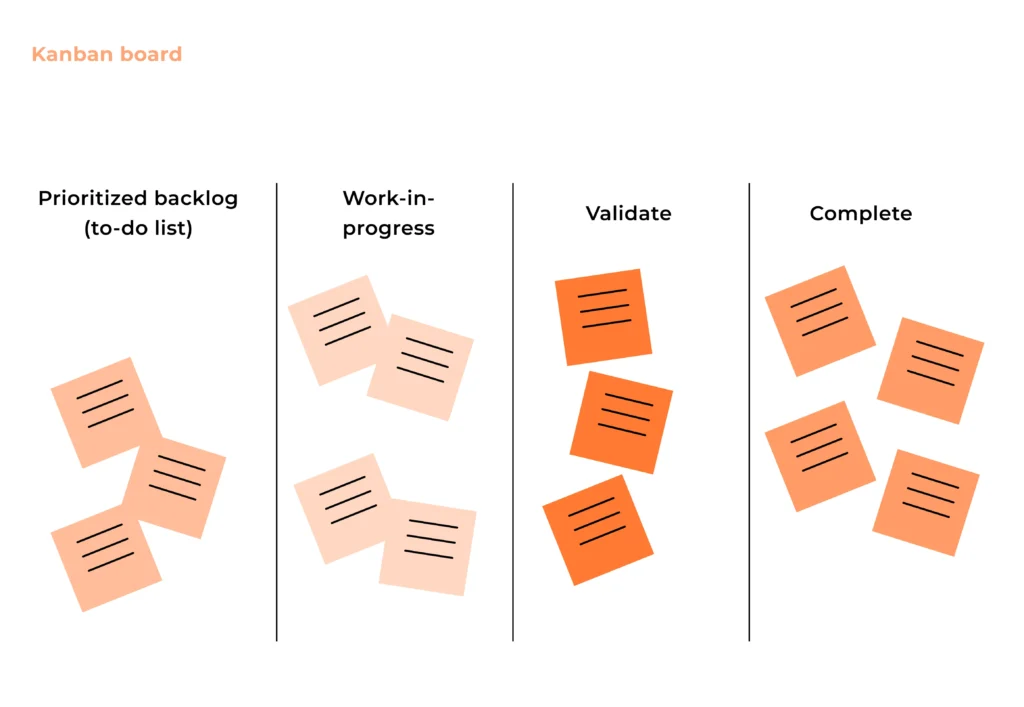

Kanban is focused on optimizing the flow of work through a system rather than organizing work into time-boxed iterations. It emphasizes continuous delivery, real-time visibility, and evolutionary change, making it particularly effective for teams dealing with unpredictable demand, operational work, or frequent priority shifts. Instead of prescribing roles or ceremonies, Kanban concentrates on how work moves, where it slows down, and how constraints affect delivery performance.

Workflow visualization and work-in-progress limits

At the core of Kanban is the explicit visualization of the workflow and the active management of work-in-progress (WIP). The goal is not to keep people busy, but to keep work flowing predictably and efficiently through the system.

- Workflow visualization makes each stage of work explicit, exposing handoffs, queues, dependencies, and blocked states. This shared visibility turns the board into a real-time representation of system health, not just a task list.

- WIP limits constrain how much work can exist in each stage at the same time, forcing teams to finish work before starting new items. This reduces context switching, highlights bottlenecks immediately, and prevents hidden queues from accumulating.

- Flow metrics such as cycle time, throughput, and cumulative flow diagrams are used to measure system performance objectively. These metrics support forecasting, capacity planning, and data-driven improvement without relying on estimates or velocity.

- Pull-based execution ensures work enters the system only when there is available capacity, aligning demand with actual team capability rather than planned commitments.

Together, these practices shift the team’s focus from task completion to system optimization and delivery reliability.

Advantages of Kanban

- Enables continuous delivery without the constraints of fixed iterations

- Adapts well to changing priorities and interrupt-driven work

- Improves predictability through flow-based metrics rather than estimates

- Exposes bottlenecks early, making systemic issues visible and actionable

- Requires minimal process change, allowing gradual adoption and evolution

- Works effectively for operational, maintenance, and mixed-type workloads

Disadvantages of Kanban

- Lacks built-in planning and review cadences, which can reduce alignment if not intentionally added

- Provides less guidance on roles and responsibilities, increasing reliance on team maturity

- Can drift into “just a board” if flow metrics and WIP discipline are not enforced

- Less effective for teams that need strong time-boxing or synchronized delivery rhythms

- Continuous flow can make progress harder to communicate to stakeholders accustomed to sprint-based milestones

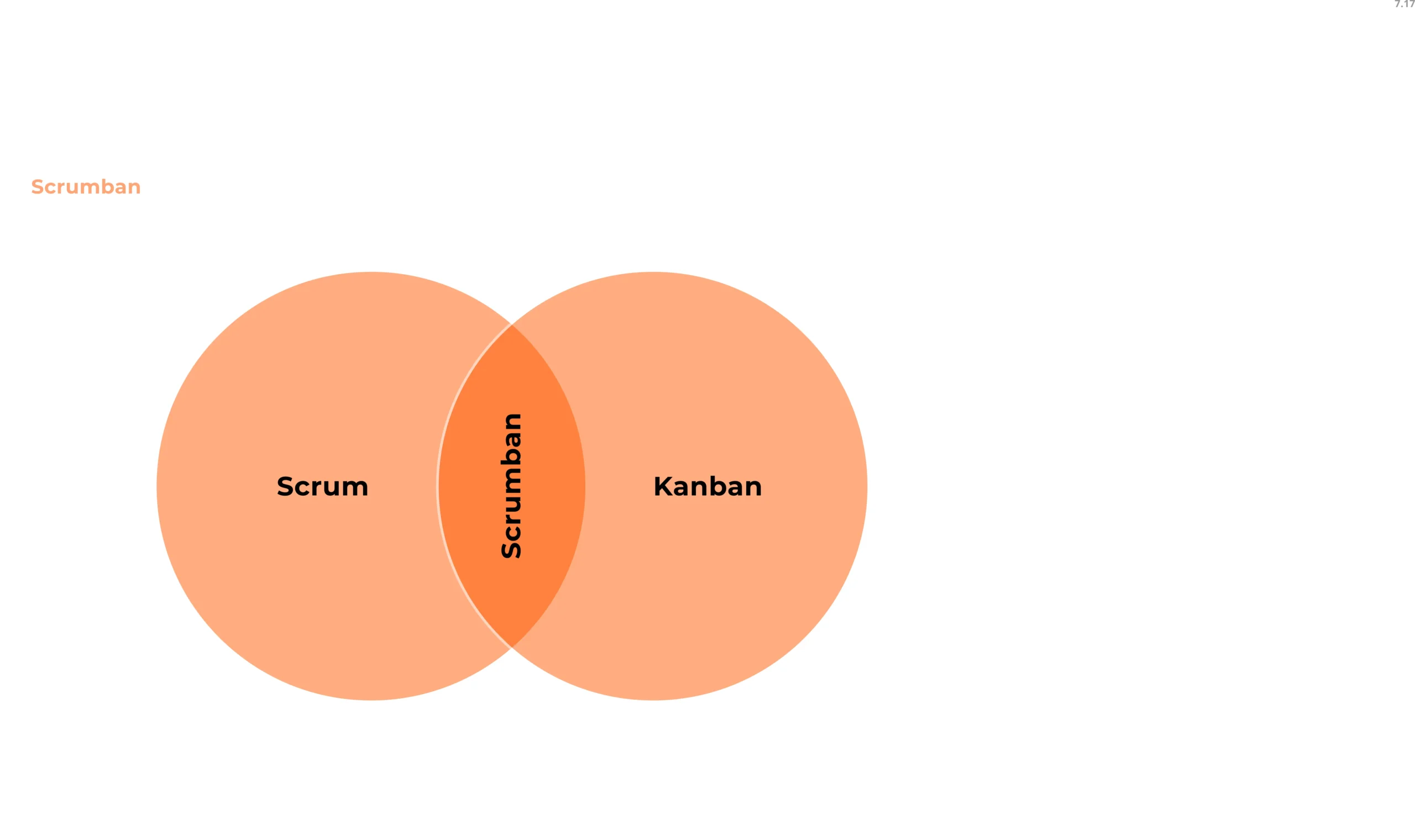

Scrumban

Scrumban combines Scrum’s backlog discipline with Kanban’s continuous flow, replacing fixed sprint commitments with pull-based execution. Work moves across a visual board with explicit WIP limits, while planning happens on demand instead of during time-boxed sprint events. This makes bottlenecks visible in real time and allows teams to reprioritize without breaking sprint contracts. It works especially well when feature development, bug fixing, and operational work compete for the same capacity.

SAFe (Scaled Agile Framework)

SAFe scales delivery by organizing teams into Agile Release Trains aligned around value streams, all synchronized through Program Increment (PI) planning cycles. Dependencies are managed upfront via shared roadmaps, architectural runways, and cross-team planning ceremonies. Economic prioritization and Lean Portfolio Management connect strategy to execution, but at the cost of heavier governance. SAFe is most effective where coordination, compliance, and predictability outweigh team-level autonomy.

Scrum of Scrums

Scrum of Scrums scales coordination, not the framework itself, by introducing a lightweight synchronization layer across multiple Scrum teams. Representatives surface cross-team dependencies, integration risks, and delivery blockers without altering how individual teams run their sprints. There are no new roles, artifacts, or planning hierarchies — just structured communication. This makes it a pragmatic choice when teams need alignment but want to avoid large-scale process overhead.

LeSS (Large-Scale Scrum)

LeSS extends Scrum by removing organizational complexity rather than adding coordination mechanisms. Multiple teams share a single product owner, product backlog, sprint, and definition of done, forcing real product-level collaboration. Instead of managing dependencies, LeSS exposes them and relies on organizational change to eliminate them. It demands strong engineering discipline and leadership support, but keeps decision-making close to the product.

DAD (Disciplined Agile Delivery)

DAD functions as a decision framework that guides teams in choosing how to work rather than prescribing what to follow. It spans the full delivery lifecycle — from inception to deployment — while allowing teams to tailor practices based on risk, compliance, distribution, and maturity. Governance, architecture, and DevOps are integrated instead of treated as add-ons. DAD fits environments where flexibility is required, but ad-hoc process design would be risky.

Agile engineering and delivery practices

Agile frameworks define how work is organized; engineering practices define how software is built. High-performing Agile teams rely on disciplined technical practices to sustain delivery speed without accumulating excessive technical debt.

Extreme programming (XP): emphasizes engineering excellence through practices such as test-driven development, pair programming, continuous integration, and frequent small releases. It is particularly effective in environments with volatile requirements and high quality expectations.

Lean software development: focuses on eliminating non-value-adding activities, optimizing flow, and empowering teams to make local decisions based on real data rather than assumptions.

Feature-driven development (FDD): structures delivery around small, client-valued features, each following a short design–build cycle. It balances predictability with incremental delivery and is effective for feature-heavy systems.

Dynamic systems development method (DSDM): provides a full-lifecycle Agile framework with stronger governance, defined roles, and prioritization mechanisms such as MoSCoW (Must have, Should have, Could have, and Won’t have). It is suited for time-critical projects requiring both agility and formal control.

Adaptive software development (ASD): emphasizes continuous learning through iterative cycles of speculation, collaboration, and adaptation. It is designed for high-uncertainty environments where traditional planning assumptions quickly become invalid.

Rapid application development (RAD): prioritizes speed through prototyping, iterative user feedback, and component reuse. It is effective when time-to-market outweighs architectural longevity, provided technical constraints are carefully managed.

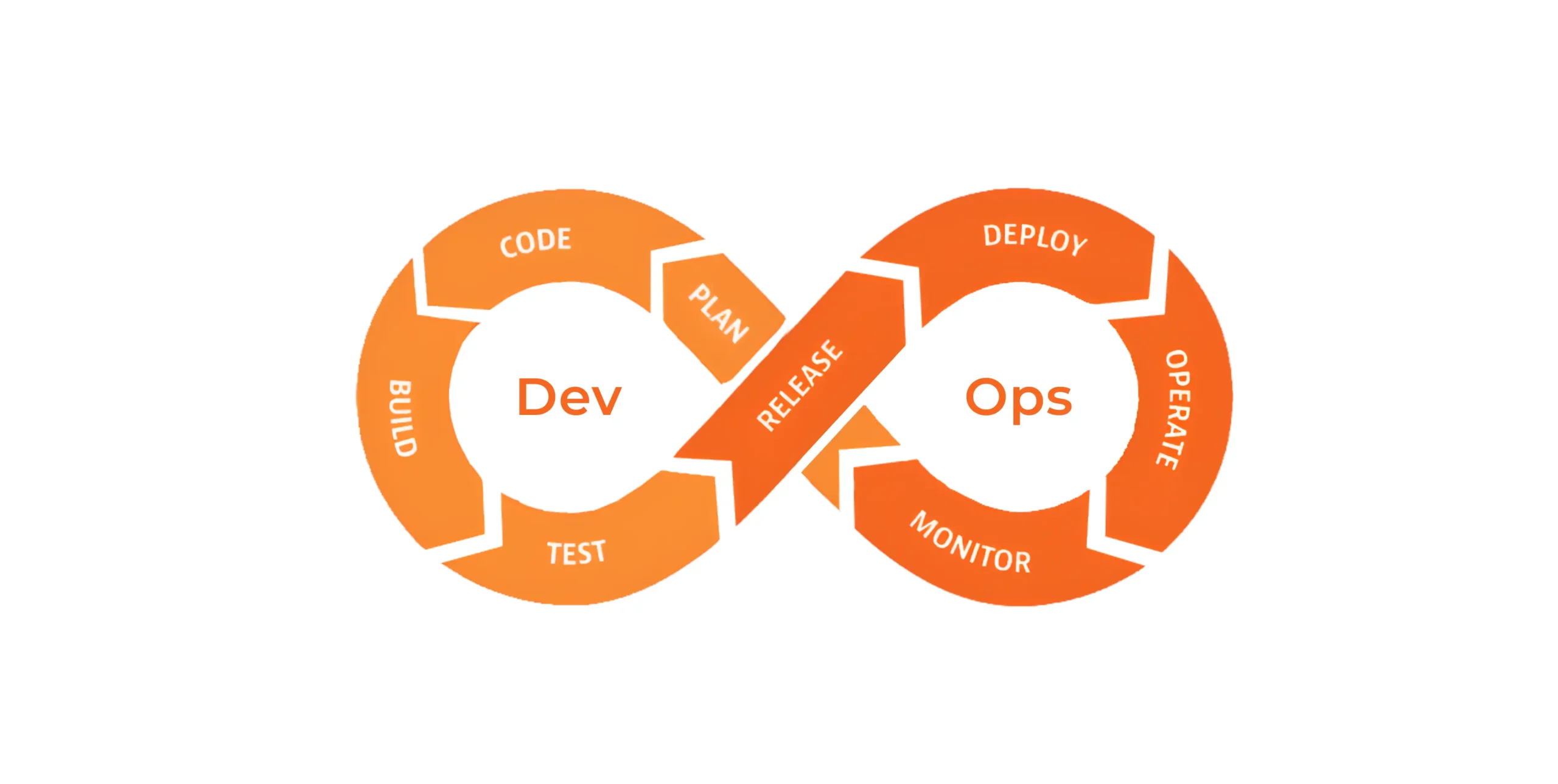

DevOps as a software development approach

DevOps is not a software development methodology in the traditional sense; it is an operating model that restructures how software is built, released, and maintained. Its primary objective is to eliminate the organizational and technical friction between development and operations by treating software delivery as a continuous, shared responsibility rather than a sequence of handoffs.

Where methodologies define how work is planned and structured, DevOps defines how software moves reliably from code to production and how teams learn from real-world system behavior. As such, DevOps reshapes team topology, tooling strategies, and delivery governance across the entire software lifecycle.

Core DevOps principles

At its foundation, DevOps is driven by a set of principles that prioritize flow, reliability, and feedback over role-based separation.

Cross-functional ownership

Teams own services end-to-end, from development through deployment and operations. This reduces handoff delays, increases system awareness, and aligns engineering decisions with production realities.

Automation as a default

Manual processes introduce variability and slow down delivery. DevOps relies on automation across integration, testing, deployment, infrastructure provisioning, and recovery to ensure repeatability and scalability.

Continuous integration and continuous delivery (CI/CD)

Code changes are merged frequently, validated automatically, and promoted through environments using standardized pipelines. This shortens feedback loops and reduces deployment risk.

Observability and feedback-driven improvement

Metrics, logs, traces, and alerts provide real-time insight into system behavior. Operational data informs both immediate incident response and longer-term product and architectural decisions.

Infrastructure as code and cloud-native practices

Infrastructure is versioned, tested, and deployed using the same discipline as application code, enabling consistency across environments and faster recovery from failure.

Together, these principles shift delivery from episodic releases to a continuous, measurable flow of value.

DevOps and Agile as complementary practices

Agile and DevOps address different, but tightly connected, parts of the delivery system.

Agile focuses on how teams plan and prioritize work under uncertainty, favoring iterative delivery, stakeholder feedback, and adaptive planning. DevOps focuses on how that work is safely and efficiently deployed and operated in production environments.

Without DevOps, Agile teams often encounter bottlenecks at release, environment provisioning, or operational readiness. Without Agile, DevOps risks optimizing deployment speed without improving product relevance or value alignment.

When combined effectively Agile drives what to build and when while DevOps ensures it can be built, released, observed, and evolved reliably.

This alignment is why most modern delivery models treat DevOps as an extension of Agile principles into deployment, infrastructure, and operations rather than a replacement for Agile frameworks.

DevSecOps (DevOps 2.0)

As systems grow more distributed and regulatory pressure increases, security can no longer function as a downstream gate. DevSecOps extends DevOps by embedding security directly into delivery pipelines, operational workflows, and team responsibilities.

Rather than positioning security as a separate function, DevSecOps reframes it as a continuous engineering concern.

Integrating security into the SDLC

DevSecOps integrates security controls throughout the software lifecycle, including:

- Automated security testing in CI pipelines

- Dependency and vulnerability scanning during build and deployment

- Policy-as-code for infrastructure and configuration enforcement

- Continuous runtime monitoring for anomalous behavior

This “shift-left” approach reduces late-stage remediation costs and minimizes the risk of security issues reaching production.

Shared responsibility for application security

In a DevSecOps model, security ownership is distributed across development, operations, and platform teams. Developers are accountable for secure code and dependencies, operations teams for hardened environments and access controls, and platform teams for secure pipelines and tooling.

This shared model improves response times, increases system resilience, and aligns security outcomes with delivery velocity rather than treating them as competing priorities.

Hybrid software development methodologies

Hybrid software development methodologies emerge from the practical reality that most real-world projects do not fit cleanly into a single delivery model. Organizations often operate under a mix of fixed constraints (e.g., regulatory, contractual, architectural) and evolving product requirements. Hybrid approaches intentionally combine predictive, plan-driven structures with iterative and adaptive execution to manage this tension without sacrificing control or delivery speed.

Rather than treating Agile and sequential methodologies as mutually exclusive, hybrid models treat them as complementary tools applied to different parts of the same system, lifecycle, or organization.

Why teams adopt hybrid approaches

Teams adopt hybrid methodologies primarily to address structural mismatches between business constraints and delivery dynamics.

In many environments, requirements definition, budgeting, compliance, or vendor contracts must be finalized upfront, while implementation details remain uncertain and subject to iteration. Pure Agile struggles in these contexts due to weak long-term predictability, while pure waterfall fails when learning and feedback are essential to product success.

Hybrid approaches are commonly chosen when teams need to:

- Maintain formal governance, documentation, and approval gates without freezing implementation decisions too early

- Deliver working increments frequently while preserving milestone-based planning and reporting

- Reduce delivery risk by validating architecture, usability, or performance early, without abandoning long-range commitments

- Support heterogeneous systems where different components evolve at different speeds (e.g., regulated core platforms alongside rapidly changing digital layers)

From an organizational perspective, hybrid models also ease transformation. They allow teams to incrementally introduce Agile practices without disrupting existing enterprise processes, tooling, or compliance frameworks.

Examples of hybrid frameworks

Several established frameworks formalize hybrid principles rather than treating them as ad hoc compromises.

Rational Unified Process (RUP)

RUP is a structured, iterative framework that combines phase-based lifecycle governance with incremental delivery. It is often described as agile-adjacent rather than fully Agile due to its strong emphasis on architecture, risk management, and documentation.

RUP organizes work into four core phases — inception, elaboration, construction, and transition — each ending with explicit milestones and decision points. Within these phases, development proceeds iteratively, allowing teams to validate use cases, mitigate technical risk, and refine architecture before committing to full-scale implementation.

This makes RUP particularly effective for large, complex systems where early architectural decisions are critical and failure costs are high. However, its flexibility comes at the cost of complexity: RUP requires experienced teams and disciplined tailoring to avoid excessive process overhead.

OpenUP (Open Unified Process)

OpenUP is a lightweight, open-source subset of RUP designed to retain its core strengths while removing unnecessary rigidity. It follows the same four-phase lifecycle but focuses on “minimum sufficient process,” making it suitable for smaller or less regulated teams.

Key characteristics of OpenUP include:

- Iterative, incremental development with short feedback loops

- Early architectural focus to reduce systemic risk

- Strong emphasis on collaboration, visibility, and shared understanding

- Micro-steps and micro-increments that allow progress to be measured daily rather than per phase

OpenUP aligns closely with Agile principles while preserving explicit lifecycle structure, making it a practical bridge between traditional governance models and adaptive delivery. It is particularly useful in environments that need discipline and traceability but want to avoid the operational weight of full-scale RUP.

Other hybrid patterns

Beyond formal frameworks, hybrid practices often appear as delivery patterns rather than named methodologies:

- Water-Scrum-Fall: upfront planning and downstream release management follow waterfall, while development runs in Scrum iterations

- Scrumban: Scrum structure combined with Kanban flow control for teams with unpredictable work intake

- Agile development with sequential rollout: iterative development paired with tightly controlled deployment or certification phases

These patterns are common in regulated industries, platform modernization initiatives, and large-scale enterprise programs where uniform methodology adoption is neither realistic nor desirable.

Hybrid methodologies are not a compromise born from indecision; they are a deliberate response to complexity. When applied intentionally and governed clearly, they allow teams to adapt where learning is required and remain predictable where stability is non-negotiable.

Choosing the right software development methodology

Software delivery frameworks are selected based on execution constraints such as team scale, dependency management, release cadence, and governance requirements. These factors determine how much structure is necessary and where flexibility can be sustained.

Project size and goals

Project size directly affects coordination complexity, governance needs, and scalability requirements. Smaller projects with narrowly defined goals typically benefit from lightweight, adaptive methodologies, while large initiatives require stronger structural safeguards.

- Small to mid-sized projects focused on speed, experimentation, or product discovery tend to perform better with Agile-based approaches, where overhead is low and feedback cycles are short.

- Large-scale or enterprise-grade projects often require hybrid or scaled frameworks to maintain alignment across teams, manage dependencies, and ensure consistency in delivery.

- When the primary goal is innovation or learning, methodologies that tolerate uncertainty perform best.

- When the goal is predictability or compliance, more structured approaches reduce execution risk.

The more stakeholders, teams, and integrations involved, the more deliberate the methodology choice must be.

Project requirements and scope

The stability of requirements is one of the strongest indicators of methodological fit. What matters is not how well requirements are documented, but how likely they are to change.

If requirements can be clearly defined upfront and are unlikely to evolve, plan-driven methodologies reduce ambiguity and rework. However, when requirements are exploratory, incomplete, or expected to evolve based on user feedback or market conditions, iterative models are better suited to absorb change without derailing progress.

A useful rule of thumb:

- Stable scope → structured methodology

- Evolving scope → adaptive methodology

Trying to force fixed-scope execution on an uncertain problem space often results in late-stage redesigns and cost overruns.

Release strategy and timeline

How and when value needs to be delivered should shape the development model.

Projects aiming for a single major release — such as internal systems, regulated platforms, or infrastructure-heavy solutions — often benefit from methodologies that emphasize upfront planning and staged validation.

In contrast, products that must reach users early and improve continuously benefit from incremental or iterative delivery models, where partial functionality can be released, measured, and refined over time.

Key considerations include:

- Frequency of releases

- Tolerance for incomplete functionality

- Dependency on external feedback

- Market or competitive pressure

A methodology misaligned with the release strategy can either slow down delivery or compromise product quality.

Team skills and experience

Methodologies do not compensate for skill gaps, they amplify strengths and weaknesses.

Highly autonomous, cross-functional teams with strong engineering and product maturity tend to thrive in Agile environments, where decision-making is decentralized and responsibility is shared. Less experienced teams, or teams with specialized, siloed roles, may require more prescriptive processes to maintain consistency and quality.

Additionally:

- Some methodologies demand strong technical discipline (e.g., test automation, CI/CD, refactoring).

- Others place heavier emphasis on process adherence and documentation.

Choosing a methodology that exceeds the team’s current maturity often leads to superficial adoption rather than real benefits.

Communication and collaboration needs

The level and frequency of communication required by a methodology must align with organizational realities.

Agile frameworks assume:

- Frequent stakeholder availability

- Fast feedback loops

- High transparency across roles

If stakeholders are rarely available, distributed teams operate across time zones, or communication must be formalized for governance reasons, highly interactive models may become inefficient or brittle.

Conversely, when collaboration is strong and decision latency is low, methodologies that rely on continuous interaction unlock significantly more value.

The question is not whether collaboration is desirable, but whether it is operationally feasible.

Budget and resource constraints

Budget structure often matters more than budget size, and understanding how costs accumulate across planning, execution, and change management is critical when evaluating different methodologies and delivery models, as outlined in this software development cost breakdown.

Consider:

- Fixed vs flexible budgets

- Ability to reallocate resources mid-project

- Cost of late-stage changes

- Availability of skilled personnel over time

When resources are constrained, methodologies that minimize waste and surface risks early tend to be more cost-effective, even if they appear less predictable on paper.

Bringing it together

In practice, most organizations do not adopt a single methodology in its pure form. Instead, they combine elements to balance structure with adaptability. The goal is not methodological purity, but alignment between process, people, and problem space.

A well-chosen methodology reduces friction, clarifies decision-making, and supports delivery without becoming a constraint in itself.

Conclusion

Software development methodologies shape how risk is distributed, how decisions are made, and where failure becomes expensive. Each methodology encodes assumptions about uncertainty, coordination, feedback, and control. When those assumptions align with reality, the methodology accelerates delivery. When they do not, it becomes a source of friction regardless of how well it is executed.

No methodology guarantees 100% success. Outcomes depend on how well the chosen approach fits the system being built, the constraints surrounding it, and the maturity of the teams applying it. Effective organizations treat methodologies as tools — adapted deliberately, governed explicitly, and evolved over time — rather than as identities or fixed playbooks.

The most resilient delivery models are those that remain structurally clear while staying responsive to evidence. In that sense, the best methodology is not the most popular or prescriptive one, but the one that makes risk visible, decisions explicit, and progress measurable without obscuring the real work of building and sustaining software.

Scale with dedicated teams of top 1% software experts across 15+ global hubs to double development velocity while maintaining cost efficiency.

Talk to an expertFAQs

1. Which methodology is best for startups?

There is no universally “best” methodology for startups — there is only what fits the startup’s risk profile, funding runway, and decision latency. Early-stage startups typically operate with high uncertainty around product-market fit, which makes rigid, plan-driven models a liability rather than a safeguard.

In practice, most successful startups use lightweight Agile or hybrid Agile–Lean approaches: short delivery cycles, continuous validation, and minimal process overhead. The critical factor is not Scrum vs Kanban, but whether the methodology allows founders and product leaders to invalidate assumptions quickly without burning engineering capacity. As the startup scales, methodologies usually evolve to introduce more structure around planning, quality, and dependency management — often incrementally rather than through a full process overhaul.

2. Which methodologies are most cost-effective?

Cost-effectiveness is determined less by the methodology itself and more by where it allows waste to accumulate. Methodologies that delay feedback tend to push risk — and therefore cost — into later phases, where changes are more expensive to implement.

Iterative and incremental approaches are generally more cost-effective in environments with uncertainty, because they surface incorrect assumptions early and reduce rework. However, in stable, well-defined domains, a structured sequential model can be cheaper overall by minimizing coordination overhead and decision churn. The most cost-efficient methodology is the one that aligns change cost curves with the actual volatility of the problem being solved.

3. What methodologies are commonly used in the SDLC?

Modern SDLCs rarely rely on a single methodology from start to finish. Instead, organizations apply different models to different phases or system components.

Commonly used approaches include:

- Sequential models for upfront analysis, compliance, or core platform design

- Agile frameworks for feature development, integration, and iteration

- Hybrid models to balance governance with incremental delivery

- DevOps-oriented operating models to manage deployment, reliability, and feedback loops

This layered usage reflects the reality that discovery, delivery, and operation each benefit from different levels of structure and adaptability.

4. What are the most widely used development methodologies today?

Today’s most widely used methodologies are those that scale across team size, system complexity, and organizational maturity. Scrum and Kanban dominate at the team level due to their simplicity and adaptability, while scaled frameworks such as SAFe, LeSS, and Scrum of Scrums are common in larger enterprises.

What’s notable is not just adoption, but blending. Many organizations run Scrum at the team level, Kanban for operational work, and DevOps pipelines for release and operations. Methodology choice has become less about strict adherence and more about assembling a delivery system that supports flow, quality, and governance simultaneously.

5. What is behavior-driven development (BDD)?

Behavior-driven development is not a process framework — it is a collaboration and specification practice that sits at the intersection of product, engineering, and testing. BDD formalizes system behavior in a language that both technical and non-technical stakeholders can understand, typically using structured scenarios written in business terms.

Its real value lies in alignment, not testing. By forcing teams to define behavior before implementation, BDD reduces ambiguity in requirements, uncovers edge cases early, and creates a shared mental model of how the system should behave. When done correctly, it becomes a decision-making tool, not just a testing technique.

6. How do development tools support BDD?

BDD tools act as an execution layer for behavioral specifications, turning human-readable scenarios into automated acceptance tests. Frameworks such as Cucumber, SpecFlow, or Behave allow teams to bind behavioral scenarios directly to test code, ensuring that documented behavior stays synchronized with the system.Beyond automation, these tools support traceability and governance. They create a living specification that links business intent to implementation and verification, which is particularly valuable in regulated or high-risk environments. The real advantage is not tool adoption itself, but the discipline it enforces: shared ownership of behavior, earlier validation, and fewer surprises late in delivery.